Why is this topic so important to me? It’s because I’ve personally been through this process. Twice. And it’s one of the hardest things I’ve had to do in my life.

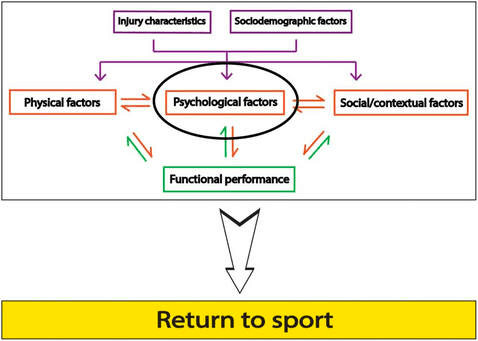

Successful return to sport after anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) reconstruction requires optimal physical AND psychological recovery. The psychological component is quite often overlooked. Fear, emotion, and poor self-esteem can have profound effects on patients’ compliance, athletic identity, and readiness to return to sport.

An athlete can be physically prepared for return to sport, but if there is fear or anxiety associated, then this process should be prolonged. If you’re a clinician, parent, or athlete reading this, here are 4 key areas to consider:

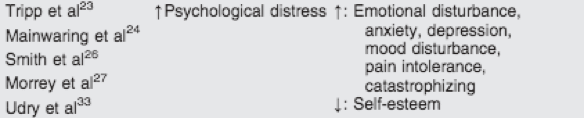

1. Psychological Distress

- Definition: upsetting or intrusive feelings that prevent a person from optimal performance

- This is where education and setting the expectations is huge. When working with an athlete, it’s important to consider this as a part of rehab. Who wouldn’t have anxiety or emotions when they can no longer play their sport and get their knee operated on. It’s completely normal. Rather than hiding it, have a conversation with your athlete. Educate them on what to expect before, during and after the procedure and for rehab. Assure them that everything will be okay and that they will get back to their sport. When an athlete knows what to expect, there’s less psychological distress associated with the process, which can significantly impact the success of the rehab and return-to-play process.

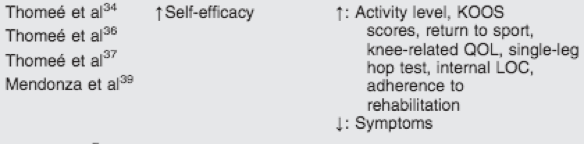

2. Self-Efficacy

- Definition: belief in one’s ability to succeed in a particular situation or execute actions

- Here’s where showing them what they CAN do versus what they can’t is a huge game-changer. It’s easy to fall into comparisons of others, especially if other friends or teammates have gone through a similar process. Highlight the fact that they have increased range of motion, can rep out multiple squats or that their quad looks strong AF. Give them the small wins to keep them engaged with the process and instill confidence within themselves.

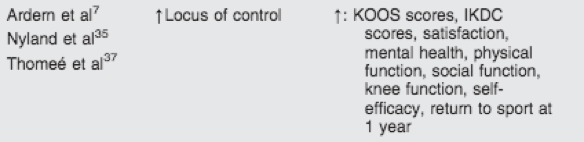

3. Locus of Control

- Definition: belief in the relationship between action and outcome; feeling like one has control

- This is usual broken down into external, internal and chance. External is believing someone else’s actions impact your outcomes. Internal is believing your actions impact your outcomes. Chance is believing your outcomes are based on fate or luck. Which one do you think should win? Internal. Which one do you think can take over? External. This is too common in the rehab process, which is why clinicians have to gut-check themselves and make sure they are facilitating independence and an internal locus of control. We’re the GPS while the patient is the driver. This should not change. It goes back to instilling confidence in the athlete and having them realize the outcome is in their control and not anyone else.

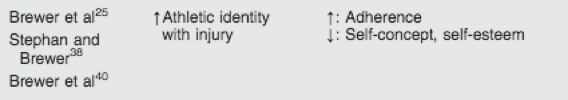

4. Athletic Identity

- Definition: degree to which one identifies with the athlete role

- This is an interesting area. The more the athlete identifies with their sport, the increase in adherence during rehab, but also decrease in self-esteem. This can be a slippery slope. If there’s less identity in sport (i.e. recreational sport compared to collegiate), then athletes are able to disconnect easier, but rehab adherence may decrease. With athletes who identify highly with their sports, the main goal is to keep them involved – whether that’s through team workouts or sessions. You can have them do upper body work and train the non-injured leg as well. This is where communicating with the coaches, family members and others involved can make a huge impact on the psychological recovery and readiness as an athlete builds to full return-to-sport.

In addition to the 4 areas above, an objective measure can be very beneficial to quantify where the athlete stands from not only a physical perspective, but psychological. That’s where the ACL-Return to Sport after Injury scale (ACL-RSI) can be helpful. The ACL-RSI is a great outcome measures to assess athletes’ emotions, confidence in performance, and risk appraisal in relation to return to sport.

Recognizing positive and negative psychological responses to injury is the first step in initiating treatment and potentially modifying beliefs through psychological interventions. It is important to identify patients who are at risk for poor outcomes because targeted psychological interventions may be successful. If you know of an athlete going through this injury and recovery process, don’t forget that there’s more to it than just what you can see.

References:

Christino MA, Fantry AJ, Vopat BG. Psychological Aspects of Recovery Following Anterior Cruciate Ligament Reconstruction. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2015;23(8):501-9.

Sadeqi M, Klouche S, Bohu Y, Herman S, Lefevre N, Gerometta A. Progression of the Psychological ACL-RSI Score and Return to Sport After Anterior Cruciate Ligament Reconstruction: A Prospective 2-Year Follow-up Study From the French Prospective Anterior Cruciate Ligament Reconstruction Cohort Study (FAST). Orthop J Sports Med. 2018;6(12):2325967118812819.

Ardern CL. Anterior Cruciate Ligament Reconstruction-Not Exactly a One-Way Ticket Back to the Preinjury Level: A Review of Contextual Factors Affecting Return to Sport After Surgery. Sports Health. 2015;7(3):224-30.

Schub D, Saluan P: Anterior cruciate ligament injuries in the young athlete: Evaluation and treatment. Sports Med Arthrosc 2011;19(1):34-43. Melissa A. Christino, MD, et al